Contributed by Irving J. Arons, Product Technology 1969-1994.

The purpose of this posting is to tell the true story of how, in the early part of the 20th Century, dedicated chemists and engineers at Arthur D. Little were put to the task of breaking the adage that you couldn’t make a silk purse from a sows’ ear. And then, some 50 years later, in 1977, how another group of dedicated scientists at the company decided to do it again, and this time show that lead balloons really could fly.The Silk Purse (1)In 1921, in order to obtain some favorable publicity for his fledgling company, Arthur Dehon Little, the founder of

Arthur D. Little, Inc., of Cambridge, Mass., decided to challenge his chemists and engineers to create "silk" from pork byproducts. The idea behind this surprising and not very practical experiment was to prove that something said to be impossible was, with sufficient effort and ingenuity, attainable. The old adage that said, "you can't make a silk purse of a sow's ear" had been used for years to discourage inventiveness and enterprise. As Arthur himself stated, "We resolved...to prove that it was false, and we have done so. We have made a silk purse of a sow's ear."

The chemists' first step was to observe the production of silk by silkworms, analyzing both the process and the product. They found that the viscous liquid emitted from ducts in the worm's head turned to silk after contact with air and that it was chemically akin to glue. Following this lead, the lab purchased one hundred pounds of sows' ears (certified to be authentic by an affidavit from the supplier,

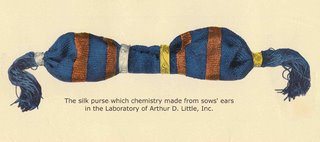

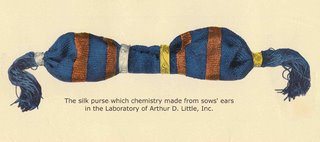

Wilson & Company, meatpackers in Chicago) and reduced it to ten pounds of glue, which was turned to gelatin by adding small amounts of chrome alum and acetone. After much trial and error the chemists hit upon a means of producing fine strands by filtering the gelatin under pressure and forcing the substance through a perforated spinneret. The resulting brittle strands, softened by bathing in a glycerin solution, were dried, dyed, and woven into cloth of "the desired soft, silky feel." From this cloth two ten-inch long "silk" purses were cut and stitched in imitation of a medieval design, used for holding silver coins in one end, and gold in the other.

The company freely acknowledged that the two "silk" purses, expensive to produce, had more value as conversation starters than as items intended for practical use. They were widely exhibited at trade shows and promotional events. "We frankly admit," the company stated, "that it is not very strong or very good silk, and that there is no present industrial value in making it from glue."

A report about the project (2) concluded: “Things that everybody thinks he knows only because he has learned the words that say it, are poisons to progress. The only way to get ahead is to dig in, to study, to find out, to reason out theories, to test them...

This making of silk purses of sows' ears was merely a diversion of chemistry at play. When chemistry puts on overalls and gets down to business, things begin to happen that are of importance to industry and to commerce. New values appear. New and better paths are opened to reach the goals desired.”

One of the purses was presented to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. The other was proudly displayed in the Boardroom of the company, at 25 Acorn Park until the company declared bankruptcy in 2002, at which time it was put up for auction.

The silk purse was obtained by Kenan Sahin, the founder of TIAX, the successor company to the old Product Technology Section of ADL, and is now part of that company’s ADL memorabilia display.

1. On the Making of Silk Purses from Sow's Ears: A Contribution to Philosophy, Arthur D. Little, Inc, 1921.

2.

"On the Making of Silk Purses from Sows' Ears," 1921, MIT Institute Archives & Special Collections.

The Lead Balloons In March 1977, Jim Birkett, a senior staff member of Arthur D. Little, came up with the idea of the company sponsoring a contest to see if any of its staff could come up with a way to break another adage – that lead balloons couldn’t fly. This was the beginning of

The Great Lead Balloon Contest.

Jim formed a blue-ribbon committee of senior management (and the daughter of Public Relations Director Alma Triner, Kim Triner – a noted Juvenile Balloon Addict) and issued a Request for Proposal (RFP), which spelled out the specifications for flying a lead balloon. Proposals were due on March 30th. In all, six teams responded with proposals of how they would solve the problem and build and fly a lead balloon. The Blue Ribbon Committee selected three approaches, announced that they would supply 0.8 mil lead foil (tissue-paper thin) and helium, and that the “fly-off” would be scheduled for Friday, May 13th.

One team, headed by Marie Chung, Warren Lyman, and Ed Dohnert, proposed to build an 8 foot diameter by 14 foot long endoskeletal balloon/dirigible, built on a balsa wood frame. It was dubbed the “Lead Zeppelin”.

A second team, headed by Jack Ennis and Sid Meyers decided on a traditional spherical, non-rigid design. They would build a scrim-reinforced lead foil outer skin, backed up by a conventional 10 foot diameter weather balloon. Their intent was to fill the space between the reinforced foil and the weather balloon with helium, allowing the air in the weather balloon to escape and eventually remove the balloon. That proved difficult or impossible to do, and the helium was eventually contained within the weather balloon – not the foil.

My team, headed by Ken Sidman, Paul Monaghan and Art Schwope, went with a cubist/Origami design, suggested by Paul Monaghan, that was basically a nine-foot cube to be folded flat and unfolded or opened only during inflation to ensure that there would be no air trapped inside, thus the “Origami” moniker. The lead foil strips were to be held together using one-sided adhesive tape, and the side seams were to be reinforced with adhesively-held scrim.

As previously mentioned, the “fly-off” was scheduled for Friday the 13th of May. But, due to excess wind conditions, the lift-off was postponed to the following Monday, May 16th.

The event was covered by the press – AP and several local newspapers, as well as by a local Boston TV station.

As the event unfolded, our cubic balloon began inflating and unfortunately, due to a technical problem, one of the side seams stuck to the bottom panel and tore a huge hole in the bottom of the balloon as it inflated. In a post mortem, we concluded that we should have put some talc over the adhesive bonded scrim to prevent it from “blocking”.

But, in fact, our cubic balloon creation did lift some 12 feet high off of the ground (see first set of photos). I know this because I was underneath the balloon, trying to place the “silk purse” in a gondola-like basket for the historic ride! A gust of wind came along, whooshing the helium out of the gaping hole and the balloon collapsed on top of me.

The spherical balloon lifted off of its launching pad, broke its tether and landed about a mile down the road off of our ADL complex.

But, the third balloon, the Lead Zeppelin (photo below) took the prize. It too broke its tether and was last seen heading toward Logan airport – about six miles from ADL. Someone on the balloon committee realized that it would show up on Logan’s radar and called the control tower to warn them about our problem. After some laughter on the part of the tower personnel, they began tracking our IFO (Identified Flying Object) and it was last spotted by a commercial aircraft out over the Atlantic Ocean headed toward Europe!

After the contest Art Schwope noted, “By definition, a balloon is an inflatable structure. The so-called winner of the contest was a design based on the lead foil being placed on a rigid, wooden frame. It was filled with helium but not inflated by helium. It was a zeppelin, not a balloon.”

The spherical balloon really wasn’t one, either. It was “built as an over layer of the lead film on top of a weather balloon. The intention was to remove the weather balloon for the contest, but that proved difficult or impossible. Thus the helium was contained by the weather balloon, not the lead foil.”

In short, there was only one, true lead balloon.(Ours.) It didn't fly high or far. But it was the only inflatable structure in which the lead film contained the helium. Yes, technically it was a failure, but true to the nature of ADLers, we considered it a success, as it was the only lead balloon and it did fly (for a short time)!

So, once again, the scientists at Arthur D. Little had done the impossible and shown that lead balloons could be made to fly.